Wired for Innovation - Guitar Pickups of the Early 1900s | PART 3: Unsung Heroes and Early Innovators

(Originally Posted: 03/03/24)

The Floodgates Open

Word spread quickly about the exciting developments in the world of electric guitar. The ‘30s and early ‘40s were something of a rat-race for pickup designs, and several patents were issued to those looking to improve the groundbreaking technology. It was an era of experimentation, and only some of the proposed designs would be recognizable to modern guitarists. Some were truly unique, such as Arnold Lesti’s “Electric Translating Device for Musical Instruments” (filed in 1935, patented 1936), which used DC current to temporarily magnetize the strings, whose vibrations would then be translated by a pair of coils (making it another early dual-coil design). Unfortunately, the need to charge the strings meant the guitar could die mid-performance, and the dangerous nature of DC current meant the risk of serious electrocution was possible to those around the instrument while it was charging (so, in a way, there were multiple chances for things to die).

In 1938, Delbert J. Dickerson invented a pickup design which featured a solid metal plate, positioned just above the strings, designed to improve the overall volume and response of the pickup. Naturally, that design impacted the playability of the instrument, but it is notable that Dickerson’s patent (finally awarded in 1940) was for an “Electric Pickup Unit for Stringed Instruments” (Pat. no. 2,209,016), revealing that the ongoing dissemination of this new pickup technology was helping its developers patent their ideas without the difficulties and complications experienced by pioneers like George Beauchamp and Paul Tutmarc. Instead of needing an entire instrument design to secure a patent, the variables within the magnetic pickup designs themselves were enough for differentiation in the eyes of the Patent Office.

An Acoustic Icon Plugs In

Another notable figure in the early pickup world was Lloyd Loar. Loar is best known today for his time working at Gibson in the late 1910s and early ‘20s, during which he designed much-lauded instruments including the L-5 archtop guitar and F-5 mandolin, widely considered to be among the finest acoustic Gibson instruments of all time. According to A. R. Duchossoir, Loar had also begun to experiment with some rudimentary electric instruments during his time at Gibson, designing a circular electrostatic pickup that was glued directly to the top of instruments. Unfortunately, none of those original Loar-designed electric prototypes survived, and all the information on them we currently have comes from Walter A. Fuller, who claimed to have discovered some of Loar’s electrics when he joined the company in ‘32, and who would later go on to become Gibson’s Chief Electronic Engineer.

The reasons behind Loar’s departure from Gibson in 1924 remain shrouded in mystery: some believe he was frustrated with management’s reluctance to move into the world of electric instruments, some claim there was tension between Loar and new Gibson Secretary-General Manager Guy Hart over the direction of the company, and some believe it was due to Gibson’s initial difficulty in selling Loar’s now-prized “Master Model” instruments. In his correspondence, Loar expressed his frustrations in working for a company that was overly focused on profits. Regardless, a few years after his departure (and after weathering the Great Depression teaching at Northwestern University), Loar and former Gibson executive/close friend Lewis Williams founded the ViVi-Tone company, just down the street from Gibson in Kalamazoo, MI. Throughout the ‘30s, ViVi-Tone produced an impressive array of electric/acoustic instruments, including a vast array of mandolin family instruments, violins/violas/cellos/double basses, claviers, and, of course, guitars.

Loar’s patented ViVi-Tone pickup design was a progenitor to the modern piezo pickup, featuring a metal plate beneath the bridge which transmitted vibrations in the strings to an electromagnetic coil hidden beneath. The company’s prolific output, combined with Loar’s seemingly endless stream of improvements, means that many surviving ViVi-Tone models can vary quite a bit in terms of features/design.

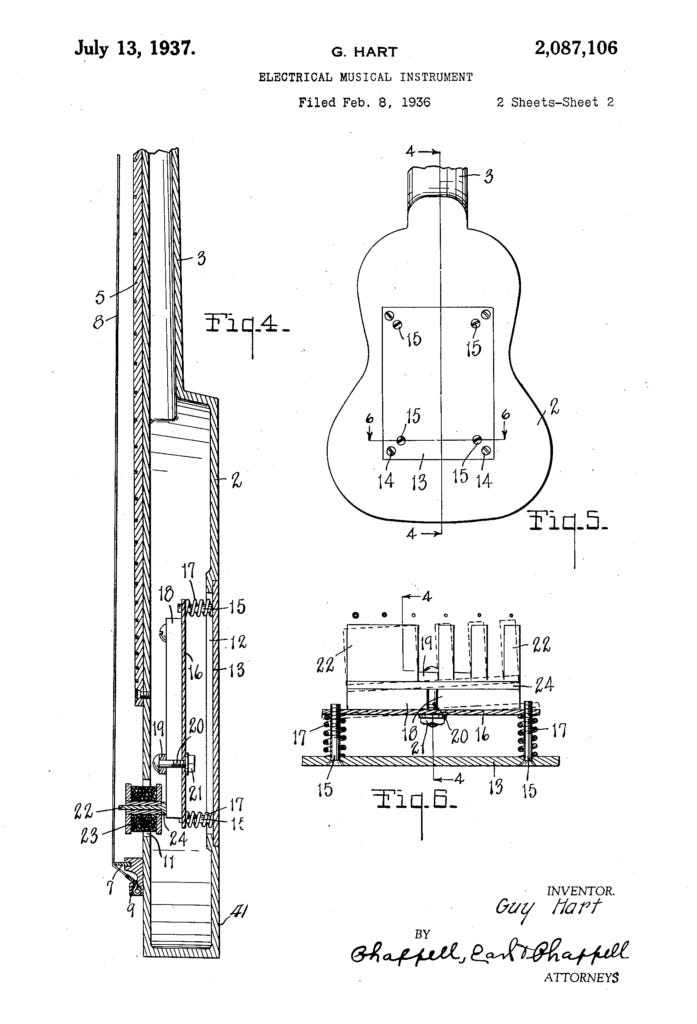

Of course, Gibson themselves eventually did get into the electric world, receiving in 1937 (filed 1936, Pat. no. 2,087,106) patent for an Electrical Musical Instrument. Similar to Beauchamp’s patent, Gibson’s was for an entire lap steel with the pickup built-in. Unlike Beauchamp’s, though, Gibson’s pickup featured a fat steel blade as a pole piece beneath the strings, with two heavy magnets sandwiching the blade at the base, and wire coiled around the blade just above the magnets. The distance of Gibson’s pickup from the strings was also adjustable, albeit in a limited capacity.

In an interesting twist of fate, the patent was officially awarded to Gibson’s Guy Hart, the same Secretary-General Manager who may or may not have butted heads with Loar over Gibson’s entry into the world of electric guitars. That being said, it’s fairly unlikely Hart had much at all to do with the actual design of the pickup, and was probably just the suit who signed off on the final patent application.

In the years that followed, a number of further pioneering pickup designs would be patented, including Gibson’s P90 with AlNiCo bars in 1946 and, after two decades of single coil noisiness, Seth Lover’s iconic Hum-Eliminating Pickup (now known simply as the humbucker) in 1957.

The history of the pickup is a feedback-laden tale of trial and error, and every musician who’s ever plugged a guitar into an amplifier owes the above pioneering inventors a significant debt of gratitude. While it’s unlikely that Beauchamp, Smith, Loar, and Tutmarc could’ve imagined the far-out, cacophonous magic that artists would work with technology they developed and inspired, none of it would have been possible without their contributions.