(Originally Posted: 02/28/24)

Few technological innovations have had as significant a cultural impact throughout the last century as the electric guitar pickup. Since their invention in the mid ‘30s, electric, amplifier-compatible instruments have spread across the world, inspiring countless musicians with their power and versatility. It’s easy to take for granted the fact that a single modern guitarist with enough wattage can fill entire arenas with bone-crushing sound, but it wasn’t long ago that the idea of a guitar being loud enough to hear over an orchestra (or even a medium-sized ensemble) was laughable.

In early 20th century America, the guitar was far from the limelight. Typically either heard backing mandolins and banjos; hidden in the rhythm section of a revue band; or as an amateur-friendly solo instrument in salons and drawing rooms, there was little need to increase the overall potential volume of the instrument. That all changed in 1928, when legendary classical guitarist Andrés Segovia arrived in the United States, shattering the public’s perceptions of what the guitar could be and opening their eyes to the possibilities of the instrument.

It’s easy to take for granted the fact that a single modern guitarist with enough wattage can fill entire arenas with bone-crushing sound, but it wasn’t long ago that the idea of a guitar being loud enough to hear over an orchestra (or even a medium-sized ensemble) was laughable.

As luck would have it, Segovia’s redefinition of what it meant to be a guitarist was perfectly timed to coincide with another groundbreaking cultural shake-up: the development of jazz in America. The slide guitar was becoming an integral part of the sound of the blues, and as jazz continued to grow in popularity, the vocal-like qualities of melodic guitar playing meant the instrument could only be constrained to the rhythm section for so long.

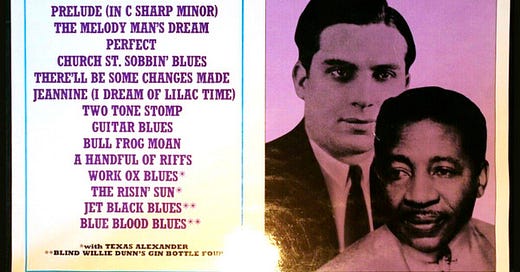

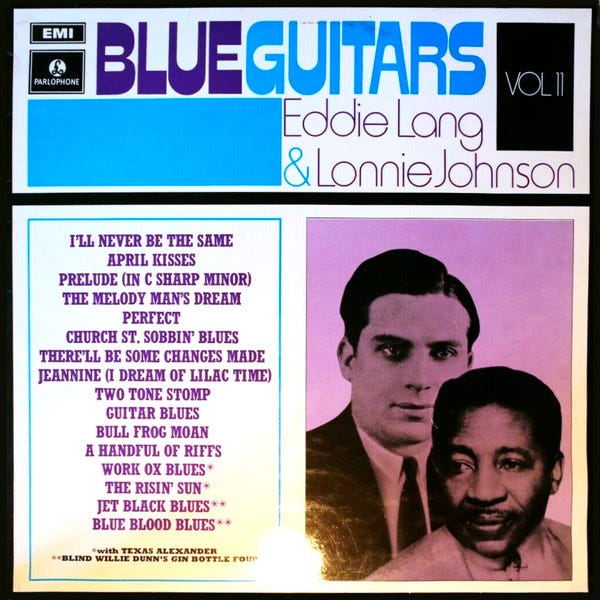

While the general public needed Segovia to realize the guitar’s potential as a solo instrument, pioneering figures in jazz and the blues were already realizing the potential it held. In fact, one year prior to Segovia’s first USA concert, the equally influential Lonnie Johnson had released his pioneering track “6/88 Glide,” one of the first records to feature nothing but solo guitar atop a backing band. Additionally, Eddie Lang was also busy recontextualizing the status of the guitar, recording some of the first guitar solos on record, as far back as 1924, with the Blue Blower’s “Deep Second Street Blues.”

Johnson and Lang met up in Chicago and were quickly inspired by each other’s talent and backgrounds (New Orleans-raised Johnson was a bluesman by trade, while Lang came from a classical background more akin to Segovia). They recorded an album together, pairing Lang’s virtuosic chording and harmonization with the singing power of Johnson’s solos. Beyond inventing the dual-guitar sound that would be heard in countless rock bands for years to come, those sessions opened the floodgates for the guitar’s new status and popularity as a solo instrument. In just a few short years, the days when guitars were considered background or amateurish instruments were far gone. Additionally, a huge boom in the popularity of Hawaiian music, which heavily featured the steel/slide guitar, further contributed to the explosion of the guitar’s popularity.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing though: while the public had discovered the joys of solo guitar, the instrument still had firm natural limitations when it came to volume. Plus, as the swing era began, the size of big bands continued to grow, easily swallowing up the guitarist without proper microphone placement and a whole host of dynamics considerations.

Fortunately, that was all about to change. The concrete origin of the “pickup” as we know it today is a contentious and fairly mysterious subject, with several independent parties claiming to have pioneered the concept, some of whom received patents for their designs and some who did not. That being said, the following is as accurate of a timeline as can be presented, considering the conflicting accounts and inconsistent documentation.

The Dawn of the Electric Guitar

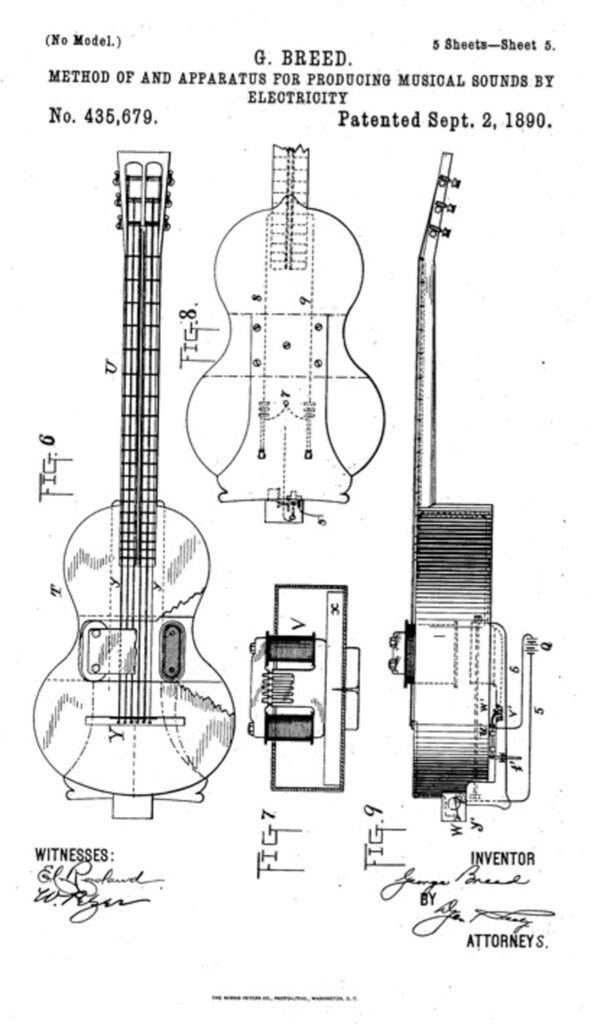

The first patented electric guitar (or at least electric fretted instrument) design goes all the way back to 1890, when a United States Naval Officer named George Breed was granted US Patent no. 435,679 for a “Method of and Apparatus for Producing Musical Sounds by Electricity.” Breed’s invention bears little to no resemblance to a modern pickup; a metal string (labeled a “sounding-wire” by Breed) would be stretched through a strong magnetic field and a direct current would be applied to said string, with the DC intermittently interrupted at a high-speed pulse. As such, the string is a component of the circuitry as well as an acoustic source, and the nature of the design means that when a string is being “played” it sustains indefinitely, not entirely dissimilar to a medieval hurdy-gurdy. If Breed attempted to manufacture or sell his design, he was unsuccessful; no examples are known to exist today, and Breed has largely become a footnote in the history of electric instruments. Breed’s patent also includes a design for an electric piano, and he was technically also the first person to ever receive a patent pertaining to such a concept. Additionally, Breed’s guitar design is notable for using metal strings, and was among the earliest guitars to ever do so. While metal strings were fairly commonplace on mandolins at the time, they wouldn’t be widely found on six-strings until Orville Gibson and the Larson brothers began to incorporate them into their designs in the 1890s.

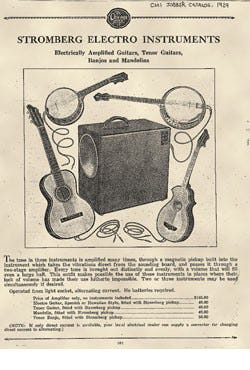

In 1928, the Stromberg-Voisinet company produced the “Electro” series of instruments, which comprised a mandolin, a four-string banjo, a tenor guitar, and a standard guitar, all of which featured a very unique pickup design with a vibrating metal reed (called an actuator) mounted on a central rod, translating vibrations from the bridge. These instruments were produced in very limited quantities, and don’t seem to have enjoyed much success; the line was discontinued sometime in mid-1929. Stromberg-Voisinet would later be renamed to the much more well-known Kay Musical Instrument Company.

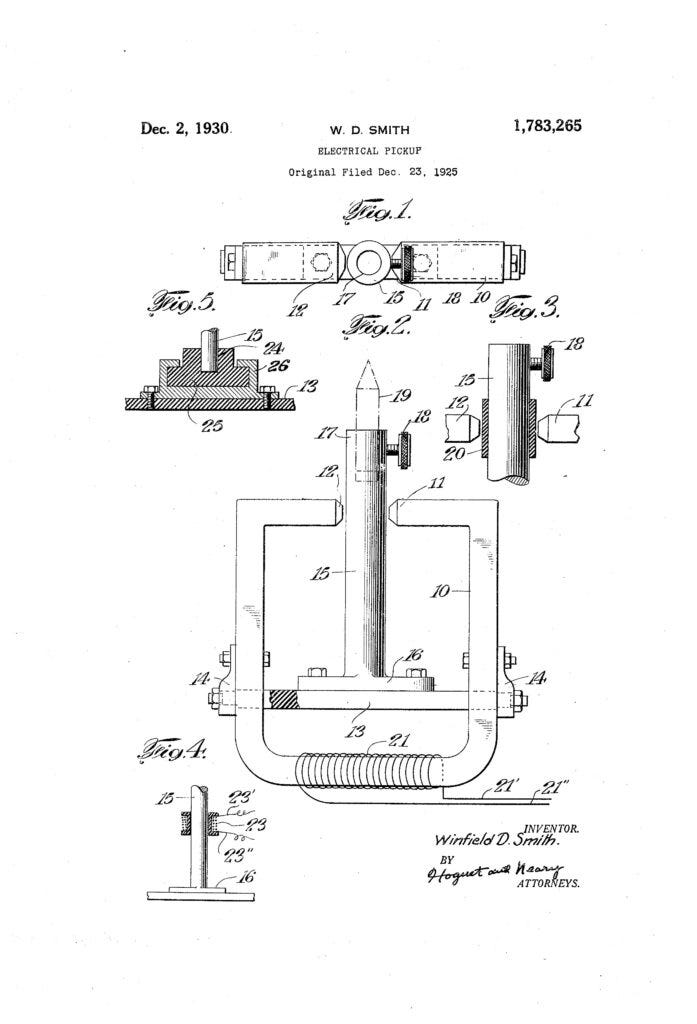

In 1930, Winfield D. Smith technically received the first American patent for an “electrical pickup,” (Pat. no. 1,783,265, filed 1925) which featured a “magnetic member” lightly held between the ends of a horseshoe magnet, with a coil wound at the base of the magnet. The positioning of the magnetic member meant that any fluctuations in air pressure caused the member to move, inducing changes in the magnetic field which in turn were translated into electromotive forces in the coil. As such, Smith’s design was actually much closer to a microphone than what we would think of today as a pickup, and was particularly susceptible to interference and feedback due to the fact that it registered sound from all directions and needed to be stood still and upright. While early guitarists may have been more stationary than the on-stage heroics their descendants would perform, such a limited design was never going to be a long-term solution.

While Stromberg-Voisinet’s Electro instruments had come and gone without much success, the groundwork had been laid for the rise of the electric guitar. In our next installment, we can finally begin to discuss the pickup designs that would become the true direct predecessors to the modern electric guitar pickup, which began to emerge in the early 1930s.

Sam Feehan